It’s in the news, the movies and, more importantly, in arts listings everywhere: cabaret and burlesque are definitely big. But they’re also easy to take for granted. Are the two words synonyms? What about variety? Or circus? Or drag? Never fear: This Is Cabaret is here to help you find your bearings in an ocean of glitter.

If you have trouble telling them apart, it’s no fault of yours. Those words get thrown around a lot these days, with little precision, and even by performers and show producers. As with all true buzzwords, journalists and PR teams want to print them as often as possible, with little time to find out what they mean.

Many people use them interchangeably, and while that may save time when picking a show to see on the weekend, it doesn’t do justice to the manifold live acts that fuel that bustling scene: Sarah-Louise Young doesn’t do burlesque, Luna Rosa doesn’t do cabaret and Piff the Magic Dragon doesn’t do either (the hint’s in the name).

Here’s your crib sheet for the next time someone asks you “what is this show you’re dressing up for, anyway?”

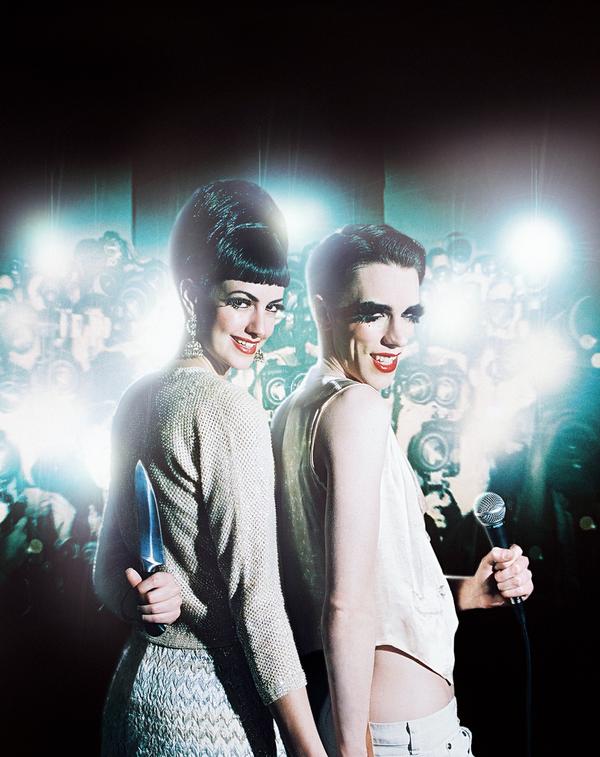

Cabaret: Musical Comedy With Audience Participation

Many cabaret acts and associated shows emulate historical periods associated with decadence and excess, especially Fin-de-Siècle France, the American Jazz Age and Weimar Germany, in no small part because of the homonymous 1972 Liza Minnelli film. But that’s incidental. A cabaret act is essentially one or more performers singing a humorous song and involving the audience directly, in some sort of dialogue, more often than not bringing patrons onstage to be made fun of. Bawdy lyrics, innuendo and politically incorrect impropriety are the norm. Some will laugh with you, some at you. Some will do other stuff as well. If Holly Penfield is in the building, there might be a riding crop involved.

The musical accompaniment may be live or not. Largely as a consequence of the small venues and low production values that have defined the genre throughout its history, cabaret acts are now often just a singer with a backing track. There’s plenty of live music going on as well, but don’t expect a full orchestra: ukuleles, keyboards and accordions are the most popular cabaret instruments, as is the kazoo, a deceptively simple wind instrument that continues to puzzle unsuspecting audiences.

Cabaret is defined by the intimate ambience in which it happens. Performers confront the public at close quarters, meandering amidst the audience, looking them in the eye and teasing them, verbally or otherwise. First-timers should be advised that there may be touching. If you’re lucky.

Representative UK acts: Bourgeois and Maurice’s piano-bar irreverence, ukulele diva Tricity Vogue’s double entendres and the taboo-busting ditties of fast-talking crooner Desmond O’Connor illustrate how cabaret uses controversial humour to engage its public. Drag performers like Jonny Woo and The Fabulous Russella are especially popular with LGBT crowds. A rising and commercially successful trend in the genre is the mash-up duo, a mix of character comedy and unexpected musical medleys seen in acts like Frisky and Mannish, Pistol and Jack and Rayguns Look Real Enough.

Burlesque: Dance With Partial Striptease

Much has been made of the Italian origins of the name as a musical-literary term for parody, but burlesque as we now know it refers to dance routines where performers gradually take off eye-catching costumes in a sexually provocative manner. Predominantly to recorded backing tracks.

The nipple tassels, pasties, G-strings and C-Strings that female dancers still rely on to cover their modesties were first used in 1920s France and America as a loophole to circumvent strict public nudity bans. Nowadays, they’re first and foremost part of the genre’s aesthetic, serving many theatrical purposes, including special effects like fire, smoke and battery-powered lights.

The mere display of flesh is seldom cause for shock or arousal in an age when live full frontal nudity is widely seen on theatrical stages and art galleries, and burlesque has evolved accordingly. The vast majority of acts are primarily humorous, including everything from tributes or parodies about celebrities and public figures to defiant statements about gender roles, beauty standards, politics or other issues.

Part pantomime, part performance art, burlesque can defy classification with its diversity. The scene’s international jargon commonly distinguishes between two broad styles: cheesecake burlesque explores vintage imagery and stereotypes of femininity, sexuality and glamour, while neo-burlesque employs freestyle choreographies and striking visual gags for shock or outrage. Boylesque, a third and more recent style, features male performers and has quickly developed strands of its own, including drag and cheesecake parodies as well as tributes to male sensuality, both gay and straight.

Representative UK acts: Miss Banbury Cross’s Marilyn Monroe tribute act, complete with a giant birthday cake, is a prime example of vintage-inspired burlesque, as are the many routines of six-strong dance troupe The Folly Mixtures. Neo-burlesquers of note include rubber-clad fetish artist Marnie Scarlet and Fancy Chance, who’s been known to metamorphose into Kim Jong Il, Prince and a giant vagina. On the male front, Lord Ritz strips like no tuxedoed, top-hat-wearing gentleman was ever meant to do, while boylesquer Cherry Loco is known for a dainty fan dance that owes nothing to the graceful ladies parading their plumes on the British circuit.

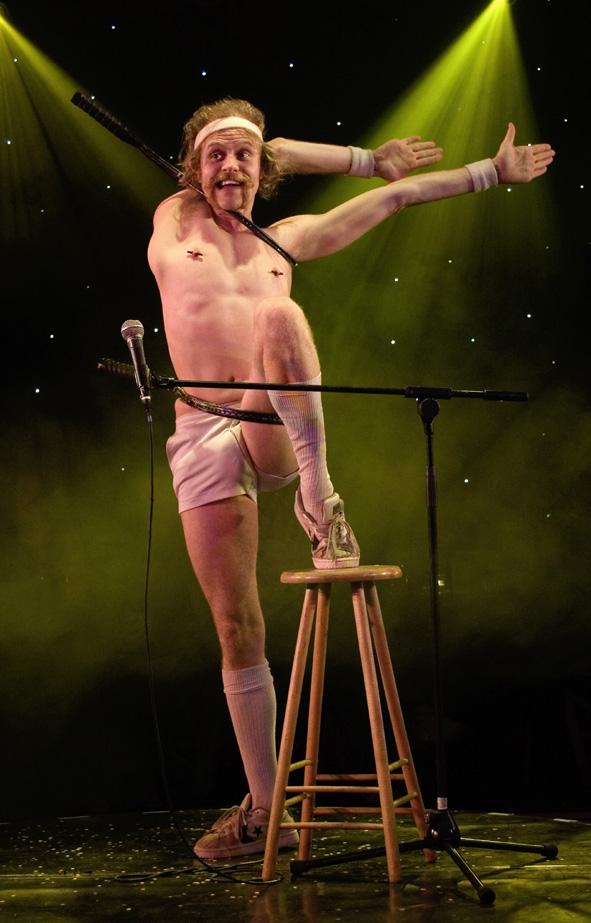

Circus: Feats of Dexterity

Older and less ambiguous than cabaret and burlesque, circus has also changed with the times. Public opinion no longer approves of trained elephants and lions on account of animal cruelty issues, so the current industry standard is to have all tricks performed exclusively by animals that can litigate and unionise.

Often neglected in the media, its athletic prowess is actually central to the so-called “cabaret boom” in the UK: it was circus show La Clique who first drew widespread mainstream media attention to the format in 2004, quickly becoming the best-selling phenomenon now known as La Soirée.

Though its thunder has been stolen by saucy musical comics and tassel-twirling bombshells, circus has left an undeniable mark in the business: contortionists, jugglers, acrobats, hula hoop performers, fire breathers and other speciality acts abound in the scene’s bills. In most evenings of prestigious London show La Rêve, the headliner is an aerialist, who swings and spins several feet above the heads in the audience. Even the most intimate shows housed in small spaces will often have a freak or two stomping barefoot on broken glass or hammering nails into their noses. Classier artists will not lick them or give them away as souvenirs once they’re through, but it’s been known to happen.

Representative UK acts: Jessie Rose combines sure moves and lively pop music into a smooth hula hoop number with an unmistakable feel-good factor. Contortionist Captain Frodo can twist his way through a tennis racket, whereas juggler Matt Hennem invariably draws wild cheer with his gravity-defying crystal ball.

Is That All There Is?

Not quite. The same stages that welcome cabaret, burlesque and circus will easily receive stand-up comedians, mind readers, ventriloquists and other distinct genres. Stage magic, though enjoying a separate scene on its own, is often bundled with circus to maximize exposure, and many magicians make the most of intimate cabaret venues by delivering close-up magic tricks from table to table.

As with any other art form, all rules and conventions can be tested by borderline and hybrid acts. Audacity Chutzpah combines the languages of burlesque and clown into an unmistakable brand of physical gags, while Sabrina Sweepstakes blurs striptease and performance art with sophisticated pieces at times melancholic, wistful, irreverent or horrifying. Few artists defy description like The Boy With Tape on His Face, who blends into both the comedy and cabaret circuits with a unique fusion of pantomime, magic and intense audience participation.

It is also not rare for more straightforward performers to have additional strings to their bows. Award-winning burlesquer Kiki Kaboom also sings, while cabaret pianist Mister Meredith often surprises patrons with songs that evolve into striptease numbers. Many burlesquers juggle or breathe fire in their skits. Acrobat Abi Collins dresses up her athletic exploits in consummate character comedy, singing and chaffing away as she puts volunteers in awkward positions, rather literally.

So What Am I Dressing Up for? A Cabaret or Burlesque Show?

If you’re in doubt, probably neither. You’ll find no shortage of self-styled “cabaret shows” these days, but they’ll be filled with burlesque and circus artists, and may even have no cabaret performers in the bill at all.

“Cabaret” is often used as an umbrella term for distinct genres of live performance, but a quick glance at show titles will reveal a rich vocabulary used to convey their range: revue, follies, carny and carnival are the most popular ones. More than capitalising on the vintage appeal of pre-War landmarks like the Folies Bergère and Ziegfeld Follies, those names point to the spot where all the genres converge into one: variety.

Similar variety traditions evolved roughly at the same time in different parts of the globe, under different names: vaudeville in the US, music hall in the UK and revue in France, among others. Aside from minor regional idiosyncrasies, they all share the same basic format. All were variety shows, as are most modern events featuring cabaret, burlesque and circus acts in the same bill.

A variety show is a series of acts by individual artists, with one or more intervals and typically performed in a relatively small theatrical space that allows for closer intimacy with the audience.

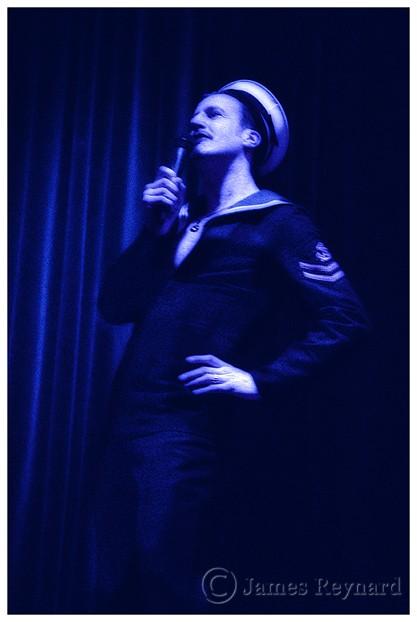

The different segments are ushered in by a compère or host – a performer in their own right whose main role is to introduce the artists and stir the public before each act. Compères are usually cabaret, burlesque or circus performers that double up in the hosting spot, whether in their shows or other people’s, and may contribute acts of their own as part of the bill, sometimes bookending the evening. They may differ in style and approach to audience interaction, but each compère imprints their show with an individual personality: they give it a face, and remain its most recognizable element to returning patrons, who will never watch the same bill twice.

Compères come in even more shapes and sizes than the acts they introduce. Benjamin Louche from The Double R Club excels in his trademark mock-philosophical banter, both unsettling and hilarious. Ivy Paige favours a blasé jazz diva persona, while Elysian Nights’ Amir Durgahee wins patrons over with a casual and unassuming demeanour, all the better to ease them onto the stage.

Specialist shows exist, of course: apart from a few guest acts, The Folly Mixtures Revue and House of Burlesque’s Shipwrecked! consist largely of burlesque acts, which makes them primarily burlesque shows. By the same token, musical comics like EastEnd Cabaret and Mr. B The Gentleman Rhymer are often seen in feature-length solo shows with nothing but their own musical comedy numbers, while the aforementioned La Soirée is predominantly a circus showcase.

Do I Really Have to Dress Up for This?

“Have to” is a bit harsh. Most shows have a dress code, but they’re largely suggestions aimed at getting patrons in the same wavelength. Venues may have dress codes of their own, which are more likely to be enforced. If in doubt, avoid jeans and sneakers and you should be fine.

For all the glitz and glamour, the truth is variety shows are self-financed independent enterprises that can hardly afford to turn away audiences on account of arrogant fashion tastes and other whims. Most regulars, especially in burlesque-heavy engagements, dress up on their own initiative. It’s part of the fun. Give it a shot, you might like it.

And never forget a stage is not a screen. They can see you, too. Up close. Perhaps closer than you’d expect. They’ll appreciate any effort to join in, sing along, cheer or wolf-whistle, and reward you accordingly. You’ll have to find out for yourself whether that’s a good thing, though, and by the time you do it, it might be too late: you may already have developed a taste for it.

Recent Comments